The Rohingya people are enduring brutal persecution by the state in Myanmar. The international community must make a stand.

Described by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as ‘one of, if not the most discriminated people in the world’, the Rohingya ethnic group are enduring unthinkable persecution at the hands of the Myanmar state. A predominantly Muslim ethnic group in a majority Buddhist country, they are looked upon as ‘illegal immigrants from Bangladesh’ by the the government, and have been the target of intense discrimination and abuse for decades.

Denied the right to vote and completely stripped of citizenship, they are a people immensely vulnerable. Recent years have seen a dramatic increase in persecution, with a military crackdown in 2017 taking the lives of thousands of civilians and prompting hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee across the border into Bangladesh. Yet despite the stark conditions facing refugees, the continued threat of persecution means that returning home is not an option. To prevent further suffering, a solution must be found.

Who are the Rohingya?

The Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic minority that practice a Sufi-inflected variation of Sunni Islam. Prior to the 2017 crackdown, Myanmar was home to around one million Rohingya, with the largest number residing in Rakhine State where they accounted for around a third of the population. They differ linguistically, ethnically and religiously from the Buddhist majority- differences that fuel the state’s resentment of them- and trace their lineage back to the 15th century when thousands of Muslims travelled to the former Arakan Kingdom.

The Myanmar government completely refuses to acknowledge the label ‘Rohingya’- a label that experts argue provides the group with a ‘collective political identity’. There is much uncertainty surrounding the etymological root of the word, but the most robust theory is that ‘Rohang’ stems from the pronunciation of the word ‘Arakan’ in a Rohingya dialect, with ‘gya’ meaning ‘from’. By asserting their connection to the former Arakan Kingdom, the Rohingya reiterate their difference from the Buddhist majority.

How are they persecuted?

The government refuses to grant the Rohingya citizenship, leaving them a stateless people. Myanmar’s 1948 citizenship law was already exclusionary in nature, but the military junta that seized power in 1962 introduced a new law two decades later that stripped the Rohingya of citizenship altogether. In 2014, Myanmar held a UN-backed national census which the Rohingya population were initially permitted to identify as Rohingya in. But after Buddhist nationalists threatened to boycott the census, the government decided that the Rohingya could only register if they identified as Bengali.

Rohingya are also discriminated against in a plethora of other ways- there are restrictions on marriage, family planning, religious freedom, education and freedom of movement. In the towns of towns of Maungdaw and Buthidaung, for example, Rohingya couples are only permitted to have two children.

Brutal crackdown

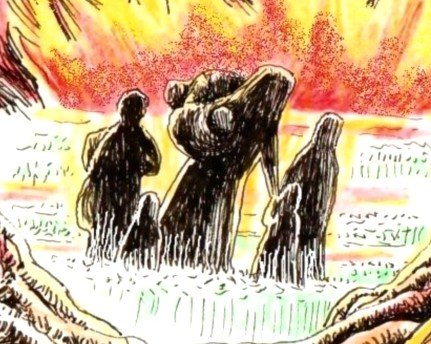

August 2017 saw violence break out in Rakhine State after a militant group known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) claimed responsibility for attacks on police and army infrastructure. In response to this, the government launched a brutal military crackdown which saw hundreds of Rohingya villages destroyed and forced nearly 700,000 to flee across the border into neighbouring countries.

According to Doctors Without Borders, the first month of violence caused at least 6,700 civilian casualties. It was also reported that the military opened fire on fleeing civilians and planted landmines close to the border with Bangladesh, while a UN fact-finding panel found ‘clear patterns of abuse’ by military personnel, including sexual abuse of Rohingya women and girls.

The immense disconnect between the Myanmar government’s version of events and those of the rest of the world is staggering. The country’s leader, former human rights icon Aung San Suu Kyi, rejected allegations of genocide when she appeared at the International Court of Justice in in December 2019, while the Myanmar Independent Commission of Enquiry (ICOE) has asserted that there is no evidence of genocide. However, a report published by UN investigators in August 2018 accused the military of carrying out mass killings and rapes with ‘genocidal intent’.

Refugee crisis

Most of those displaced by the violence have sought sanctuary in Bangladesh, a country in many ways ill-equipped to handle such a substantial influx of vulnerable refugees. As it stands, there are upwards of 900,000 Rohingya refugees residing in the country, many of whom are situated in crowded camps in Cox’s Bazar district, a region home to the world’s largest refugee camp.

According to Human Rights Watch, around 400,000 Rohingya children in the Bangladesh camps are without access to education. The Bangladeshi government prevents Rohingya children from enrolling in schools in local communities outside the camps, and bars UN humanitarian agencies from providing them with a formal education.

Outbreaks of disease are rife, with health organisations warning of possible outbreaks of measles, tetanus, diphtheria, and acute jaundice syndrome. The prevalence of communicable disease is inextricably linked to the poor sanitation in the camps- Reuters holds that around 60 percent of the available water supply is contaminated.

Yet the ultimate tragedy is that despite these abject conditions, staying in the camps remains a favourable option to returning home. UN investigators have warned there is a ‘serious risk that genocidal actions may occur or recur’ in Rakhine State, and to quote CFR’s Joshua Kurlantzick, ‘as grim as the situation is for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh… their prospects back in Myanmar are even worse’. In late 2019, Bangladeshi and Myanmar authorities agreed on a deal to repatriate several thousand displaced Rohingya, but all refused, with Rohingya leaders stating that they will not return until their citizenship rights are guaranteed.

The misery and injustice heaped upon the Rohingya cannot continue. To avert further horrors, the international community must take a stand.

Cameron Boyle is a political correspondent for the Immigration Advice Service, an organisation of immigration solicitors based in the UK and Ireland.

Article Discussion