Education reformers often argue the need for ’21st-century education.’ Do their calls for an education revolution stand up to scrutiny?

The issue of education reform is ever-present when the topic of education is mentioned. It is often argued that the current school system, and by extension school curricula, are outdated and not fit for the demands and realities of the 21st century. To ready students for the world in the 21st century, a new approach to learning, based on skills rather than knowledge, personalised learning and new technologies is required, according to many education reformers. These ideas have been popularised by public education researchers and experts such as Sir Ken Robinson and Pasi Sahlberg.

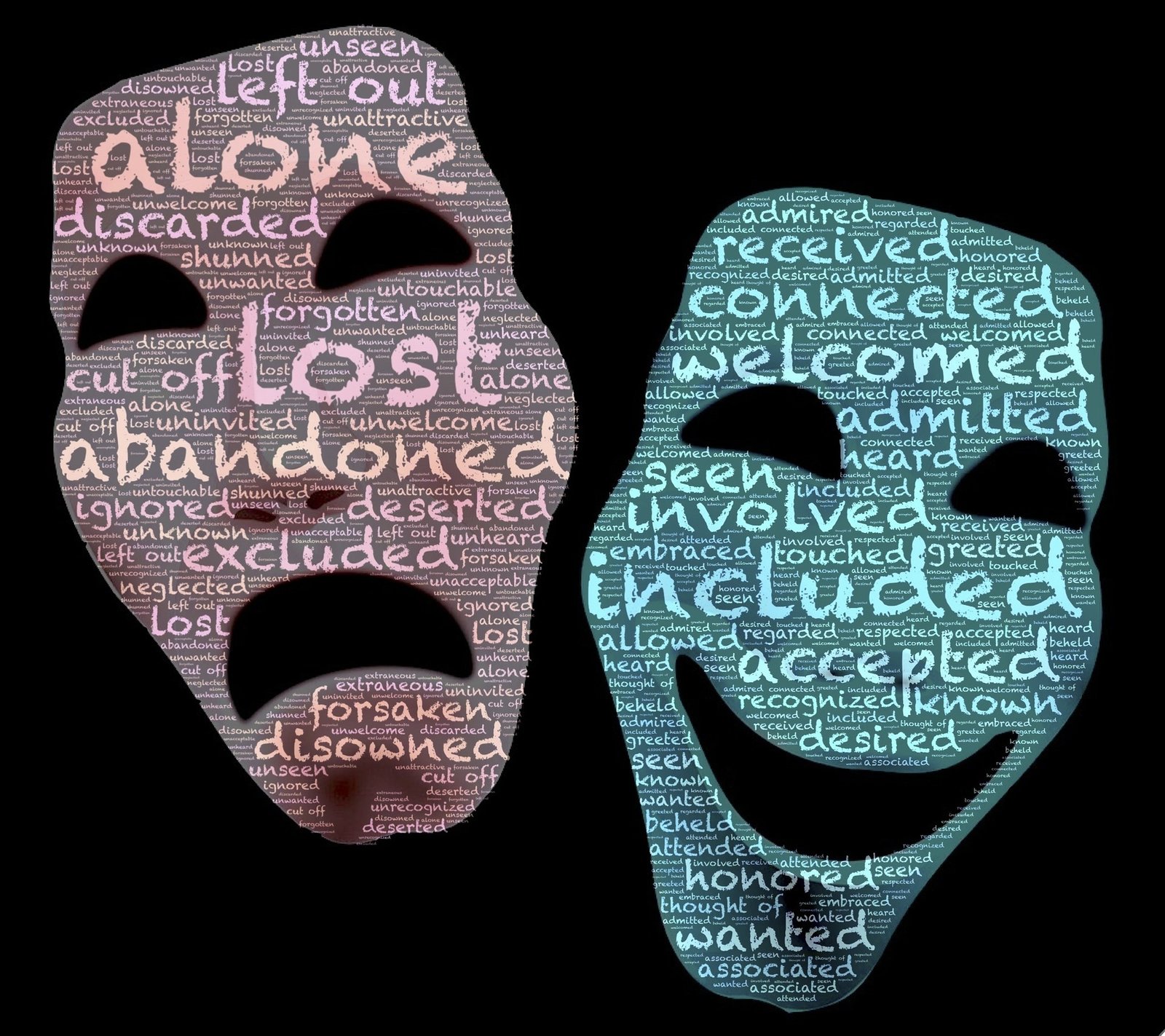

One of the significant aspects of 21st-century that most proponents agree on is an emphasis on so-called soft skills. Soft skills are defined as interpersonal, or people skills, as well as other personal attributes. In the context of 21st-century skills, this includes skills and attributes such as collaboration and teamwork skills, the ability to think creatively and critically, the ability to problem solve and leadership skills. Many educators who favour this form of 21st-century education often argue that the current curriculum and the content it teaches leaves students ill-prepared for the modern workforce. It is argued that by focusing less on content, and more on these soft skills, education will become more relevant and help students transfer into the job market.

Personalised learning is another element of 21st-century education. A customised learning experience, according to its proponents, is learning which takes into account a student’s interests, preferences and learning style. The notion of learning styles is based on the idea that students learn better based on the format in which content is presented, such as auditory, visual or kinesthetic. While ideas of learning styles are popular among teachers, the science behind the research is disputed. The evidence base for learning styles is relatively weak, while many substantive studies against the idea have been produced. Thus, the concept of learning styles is often referred to as a neuromyth, a popular notion about cognitive science that is untrue.

Personalised learning also takes the form of students studying at their own pace and on topics that interest them, as opposed to a more traditional curriculum with standard subjects. Countries such as Finland have been especially enthusiastic about taking up this form of learning. Learning becomes more student-driven and focused, with teachers acting as ‘facilitators’ as opposed to instructors. The role of the teacher, thus, changes considerably in this system. Traditional, direct-instruction based systems of teaching are minimised. Direct instruction is based on a sequenced curriculum, explicit teaching of a concept and mastery learning, where students continue to practice a concept until they have demonstrated the required level of mastery of it. This form of learning is often derided by 21st-century education proponents as not being engaging for students, or sufficiently developing critical thinking skills. However, direct instruction, according to recent studies, has shown to be highly effective for novice learners (i.e. schoolchildren) in learning about new concepts. John Hattie’s review of over 300 research studies has shown Direct Instruction to have an above-average benefit to learning for students of all age groups. Student-based practices, on the other hand, while still having some benefit, were less beneficial, and were most helpful only in certain circumstances.

The use of technology, unsurprisingly, is another major aspect of 21st-century education. The rapid pace of technological development has had a significant impact on how teaching is delivered within schools. The prominence of computers, for instance, has had an enormous impact on lesson delivery, as has the ubiquitous presence of smartphones. This presents a challenge for schools: students are often more versed in new technologies than teachers are, making taking full advantage of new technologies in effective ways more difficult. Related to this, in recent years many schools have placed an additional emphasis on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects as a way to prepare students for the future job market. As well as providing relevant subject-specific skills, proponents of STEM subjects and learning argue that studying these subjects allows students to develop crucial problem-solving skills. Targeted, effective use of technology relevant to a subject and learning experiences can lead to useful learning experiences as well as reduce the time spent on the bureaucratic aspects of teaching, such as marking.

The technology argument goes in hand with arguments about employability. A popular refrain among advocates of a 21st-century education and curriculum is that it has to prepare students for ‘jobs of the future.’ With the pace of change in society, such a claim makes sense when initially heard. A closer look at this claim shows that it is not necessarily an accurate one. For instance, a statistic claiming that 65% of future jobs have not been invented yet was shown by the BBC program ‘More or Less‘ to have been falsified. Furthermore, the jobs of the future are often roles which are already performed in society, just in different ways. For instance, the job of an Uber driver is considered a ‘future job’, even though the job of being a driver is not a new one. Therefore, caution needs to be exercised when reconfiguring the curriculum in the name of ‘future jobs.’

Critics of 21st-century education and curriculum also argue that by focusing on soft skills, more fundamental skills such as reading and writing are neglected. These critics have a point – literacy and numeracy levels in many countries, such as Australia, are trending downwards. The decline in fundamental skills also has implications for the development of critical thinking skills. Recent research has shown that the ability to think critically is domain-specific, rather than a skill that can be developed in a general sense. In a 2008 article entitled ‘Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard To Teach?’, education researcher Daniel T. Willingham states,

“If you remind a student to ‘look at an issue from multiple perspectives’ often enough, he will learn that he ought to do so, but if he doesn’t know much about an issue, he can’t think about it from multiple perspectives … critical thinking (as well as scientific thinking and other domain-based thinking) is not a skill. There is not a set of critical thinking skills that can be acquired and deployed regardless of context.”

The goal of improving critical thinking skills is an important one. For it to happen, however, a focus must once again be placed on content and subject-specific skills rather than a more generalised push for critical thinking, which is divorced from its necessary context.

The appeal of a 21st-century education which emphasises things such as student-centred learning and employable ‘skills-based’ curricula is understandable. After all, who wouldn’t want their child to receive a tailored education? It is a notion which sounds very good when one first hears of it. Upon closer inspection, however, many of the claims made by proponents of 21st-century education, while laudable, do not necessarily stack up with the research and evidence on the issues. While the 21st-century will inevitably change the way teaching is delivered, it is important not to assume that new forms of education or teaching delivery are superior to those currently in place. Before advocating for an education revolution, it is essential that the proper, evidence-based case is made to do so. A critical examination of 21-st century education as it is often argued for does not currently hold up to scrutiny.

Article Discussion