By Katie Barker

The Chancellor of the Exchequer has announced a £400 million extra funding for schools to purchase those ‘little extras’. But, is this what schools need?

The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s recent budget announcement of £400 million of extra funding for schools was remarkable in the way in which it united, in anger, both teachers and senior leaders in education. Phillip Hammond claimed the funding would allow schools to purchase those ‘little extras’. Following this statement, there was an immediate backlash. The hashtag #littleextras on Twitter was full of both sarcastic replies and also ones showing the harsh reality of school life, as well as major problems that schools around the country are facing, such as leaking roofs and insufficient infrastructure. Major unions including the National Education Union are holding indicative ballots for strike action.

Why the anger? Surely any increase in funding is to be welcomed, or so one would expect. On average, primary schools will receive an extra £10,000 each through this extra funding, whilst secondary schools will receive £50,000. Obviously, this is money that will be welcomed by schools. It is, however, a drop in the ocean in comparison to the real terms funding cuts that schools have endured over the past eight years. The Institute for Fiscal Studies reported that funding in England has fallen by eight percent since 2010, partly due to cuts to Local Authority funding and partly due to increasing pupil numbers. The Chancellor’s choice of the term ‘little extras’ therefore, seems at best, tone-deaf, at worst a suggestion that teachers can be bought off with a little extra ‘housekeeping’ money from he who controls the purse strings.

For a long time, the official Department for Education (DfE) line had been that overall spending on schools was rising, and that the UK was, in fact, the third highest spender on education in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This, however, was challenged by the OECD which showed that the figures quoted by the DfE included money spent by parents on private education, as well as university tuition fees. Naturally, this incensed Headteachers who had been fighting against the governmental narrative that spending on education was at a record high. Gaslighting may not be too strong a term for how the teaching profession viewed these disingenuous claims. It seemed that the government was attempting to perpetuate the myth of ‘whinging teachers looking for any excuse to explain their own failings’.

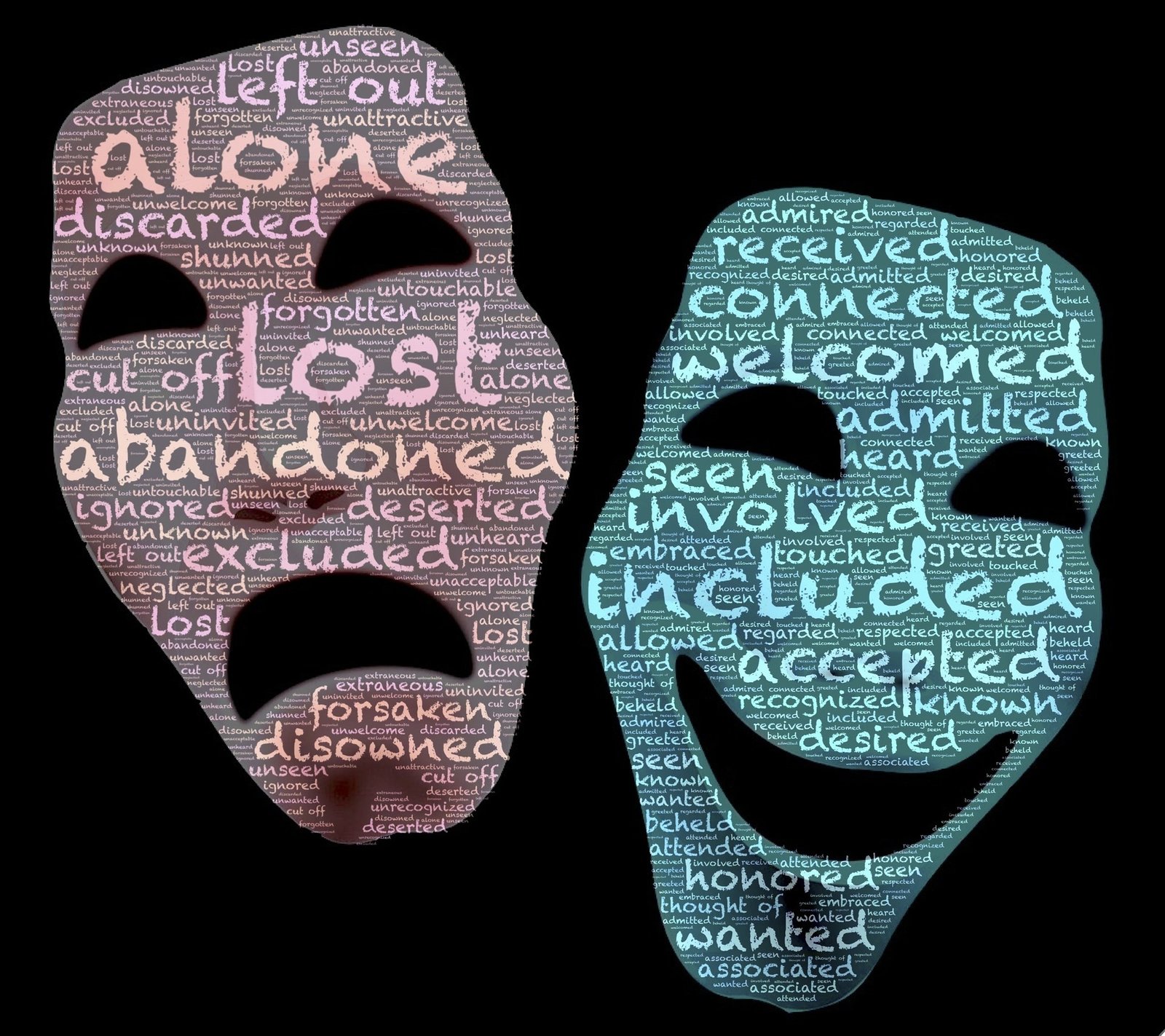

What has been the impact of the real-terms cuts in spending? At a general level, staff, curriculum and pastoral support have been negatively impacted by these cuts. Estimates suggest that around 15,000 teachers and teaching assistants have moved away from secondary schools in the last two years, just as a population bulge of 4,500 extra students moves from primary to secondary education. These secondary schools are losing the equivalent of 2.4 classroom teachers, 1.6 teaching assistants and 1.5 support staff each. Clearly, this will impact on class sizes and support for young people, particularly those with Special Educational Needs. The loss of staff and lack of funding is also leading to schools reducing their curriculum offer, with less popular options subjects being withdrawn if class sizes are too small to make it economical to offer them. In terms of pastoral support for students, school counselors and learning and behaviour mentors are often amongst the first staff to be made redundant, at a time of increasing mental health concerns amongst young people. For many in education, a perfect storm is brewing.

Moving from the general to the particular, I must confess to having a dog in this race. I am a teacher. I work in a secondary school in a very deprived area of a relatively deprived town. This means that the funding cuts hit all the harder as we cannot hope for parents to make ‘voluntary’ donations as many schools are now doing, with Freedom of Information requests made by Channel 4 news suggesting that schools are being subsidised by parents to the tune of some £150 million a year. Other schools, including one in Theresa May’s own constituency, have asked for specific donations to pay for stationery and books. Equally, the expectations of schools in deprived areas are also higher, with school often providing ‘extras’ for students such as revision guides and no-cost school trips, which are no longer viable.

The school I work in has lost teaching staff. We are lucky in that there were no forced redundancies and the savings were found through ‘natural wastage’, that is to say, staff retiring or moving on. However, the impact on the school and the students is the same. Larger class sizes, up to 33 students per class in some subjects, crammed into classrooms designed for, at most, 30. Students sitting three to a desk in some cases. Clearly, this has an impact on how much individual attention can be provided for young people within the lesson, as well as adversely affecting teacher workload in terms of marking and feedback.

Perhaps worse for students with Special Educational Needs has been the loss of teaching assistants. Now only students who are placed on an Education, Health and Care Plan (the replacement of the old ‘Statement’) which states their entitlement to one-to-one support receive the attention of a teaching assistant. The first £6000 of support funding has to come out of the school budget before additional funding from the Local Authority is provided. In the past, those students with a known need (marked as ‘K’ on the register of Special Educational Needs) would have had support at least some of the time, depending on their particular need. The school struggles to fulfill its statutory requirements as it is, so support for these children is euphemistically stated as ‘quality first teaching in the classroom’ but it is clear that they would have benefitted from more support in the past.

In terms of the curriculum, whilst the school has maintained the arts subjects that some schools have cut, options at GCSE level have been reduced. Whereas in the past Music was a GCSE option chosen by around ten students a year, that has become too costly to run so those students now no longer have the opportunity to study Music at GCSE. Similarly, the range of technology options has been narrowed down, with students funneled into Food Technology or Product Design as specialist engineering and textiles teachers have not been replaced. At A-Level, classes per subject have been reduced, meaning that some combinations of subjects are impossible, and also increasing teacher workload as classes of 25 to 30 are now the norm. Narrowing of options is clearly detrimental to students, but necessary in the attempt to make the budget balance.

Perhaps the most damaging impact has been in terms of pastoral support. The school had already moved to non-teaching Heads of Year, who are paid considerably less than qualified teachers, but these staff are now not being replaced when they leave. Instead of seven Heads of Year with a pastoral manager, there is now just one per key stage. Clearly looking after the interests of between 250 to 325 students each is a challenging role and makes it harder to develop relationships of trust with young people that may lead to disclosures. Equally, the school used to employ a counselor three days per week for those experiencing mental health difficulties, but that funding has ceased, and students are now advised to visit their GP and seek help through the underfunded and oversubscribed Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

Our students deserve better, they deserve more than throwaway comments about ‘little extras’.

Behaviour support has also been reduced. The school used to employ a behaviour mentor who would run intervention sessions with students who found it difficult to conform to behavioural norms. Sometimes this would involve removing students from mainstream lessons, which was beneficial for the student themselves, the other young people in the classroom and the teacher. However, there is no longer anyone in this role, meaning that if students do have to be removed from the classroom, they are instead placed in ‘isolation’ outside of the Headteacher’s office, completing worksheets and neither partaking in serious learning nor addressing the causes of the behaviour that resulted in their removal from the classroom in the first place. Clearly, this has a detrimental impact on behaviour and the general atmosphere in the school has declined as ‘isolation’ does not contribute to improving the student’s behaviour, nor it helps the school address the problem efficiently.

I have been a teacher for well over a decade. I love many aspects of it. But I am exhausted by it. Funding cuts have made a hard job impossible. I have always supplemented the resources provided by the school. I have purchased sanitary products, breakfast foods, and stationery for my form group, but now I have to try to source uniform, shoes, bags – things that school used to be able to ‘find’ money for. Squaring the circle with ever-dwindling resources has become an impossible job. I leave at Christmas. I will miss it, but for the sake of my health, I have to leave it behind. This is the reality of working in schools in 2018. Rewarding, challenging but ultimately unsustainable. I’m not the first, and nor will I be the last, teacher to leave the profession. Our students deserve better, they deserve more than throwaway comments about ‘little extras’.

Article Discussion