As China implements its Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese money and immigration spreads out across Southeast Asia. We take a closer look.

Much of human history, posits historian Niall Ferguson in his recent book The Square and the Tower, can be viewed as a history of networks and hierarchies. When analysing the burgeoning economic relationship between China and Southeast Asia, currently two of the most dynamic economies in the word, it is useful to view this relationship through historic and contemporary networks of migration, trade, capital, production, and infrastructure.

Much of Southeast Asia’s history is intertwined with that of China’s. While the Indian subcontinent influenced the region culturally and religiously, China’s influence was through demographics. An estimated 30 million-plus people of Chinese descent reside in Southeast Asia today, descendants of settlers who arrived from the mainland in multiple waves from the 10th century onwards to escape instability and poverty. The last significant wave would arrive in the later nineteenth century under colonial rule, to work as labourers in the tin mines and plantations. In the city-state of Singapore alone, Chinese migrants were able to form the dominant group.

While many migrants arrived in Southeast Asia’s ports dirt poor, they would quickly ingratiate themselves into their new homes and come to dominate local commerce. Many of Southeast Asia’s Chinese diaspora would establish themselves as a ‘middleman minority’ (as described by economist Thomas Sowell), serving as intermediaries between producers and consumers through specialization in retail trade and moneylending. Many of these Chinese enterprises would subsequently develop from petty retail stores to large family-owned conglomerates, dominating much of the region’s private sectors.

Many of Southeast Asia’s richest tycoons are and were ethnic Chinese, with household names such as Robert Kuok from Malaysia, the late Liem Sioe Liong from Indonesia and the late Henry Sy from the Philippines gaining legendary status through their rags-to-riches stories. Indeed, the economic outperformance and disproportionate influence of the diaspora Chinese has often fuelled resentment from the native populace, resulting in historic instances of state discrimination, pogroms and violence in countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

Much of the community would lose contact with their ancestral homeland as China closed itself off during the brutalities of the Cultural Revolution. As Deng Xiaoping began China’s opening up in the eighties, the capital and technology needed for China’s subsequent economic takeoff would be found in the hands of their overseas compatriots. Indeed, the majority of inward investment into China during the first three decades of opening up would come from the overseas Chinese; namely from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia. In 1989, overseas Chinese investments into China amounted to $30 billion, with more than 10% of this coming from Southeast Asia. The term ‘bamboo network’ entered economic terminology – referring to the intricate networks of ethnic Chinese-owned conglomerates with businesses spread across Southeast Asia and Greater China.

ASEAN’s trading ties with China have only grown significantly since. Since 1996, ASEAN total merchandise trade with China expanded 26 times from $16.7 billion to $441.6 billion in 2017, while its percentage share of Southeast Asia’s total trade rose from 2.5% to 17.2% in the same period. China has remained Southeast Asia’s largest trading partner since 2012, while the latter has been China’s third largest partner since 2015. China also accounted for Southeast Asia’s third largest source of foreign direct investment in 2017. Southeast Asia’s export-reliant economies have become key supply nodes within the regional production networks that centre on China; largely exporting intermediate goods and commodities to the mainland to be processed into finished products for export to the US.

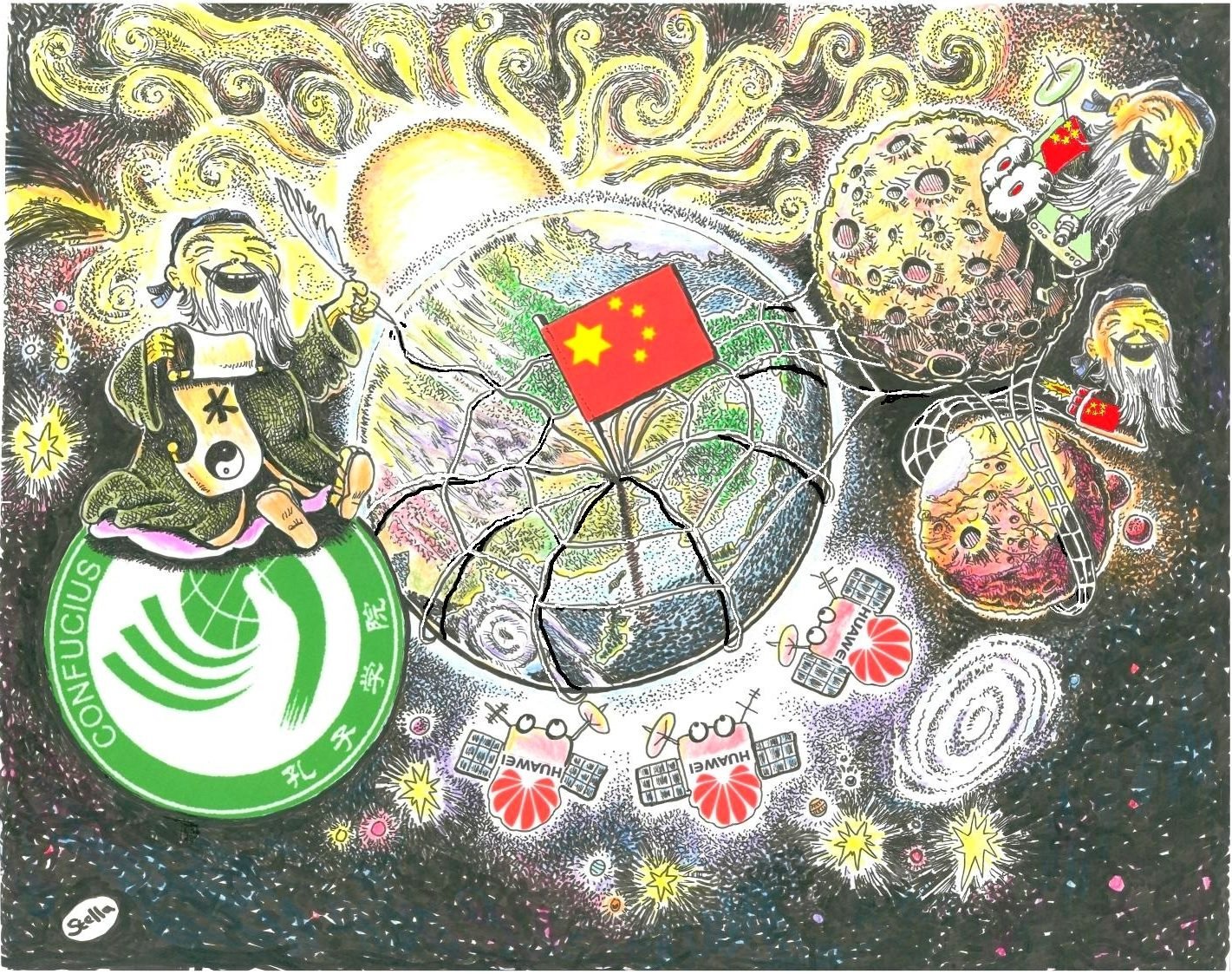

As such, it is unsurprising that Southeast Asia has become one of the main beneficiaries of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious global program launched in 2013 to link China with new markets worldwide through a vast network of infrastructure projects spanning 125 countries. According to the American Enterprise Institute, BRI-related investments and construction projects in ASEAN between 2013 and 2018 totalled $145.33 billion, or 24% of the global total (making ASEAN the largest BRI recipient). China’s push for greater global connectivity has been welcomed in a region where poor infrastructure hinders future growth – in 2017 the Asian Development Bank estimated that Southeast Asia would require $2.8 trillion in infrastructure investments between 2016 and 2030.

Chinese investments into Southeast Asia has sparked new waves of southward migration from the mainland. While Chinese migrants once arrived on Southeast Asian shores with only a ‘mat and pillow’ in hand, their modern counterparts bring skills and cash. Coinciding with increasing inflows of Chinese goods and capital has been the inflow of Chinese entrepreneurs, laborers, and tourists. One count of Chinese migrant stock numbers in BRI regions between 1990 and 2015 saw Southeast Asia’s numbers rise from 634,278 to 709,996. A separate study predicted Chinese tourist numbers into Southeast Asia would treble from 23 million in 2017 to 72 million by 2035.

For many Southeast Asians, this new inflow of Chinese migrants has been one of the more visible and unnerving aspects of closer ties with Beijing. Many come as a result of large Chinese projects, whose agreements allow Chinese companies to import in their own workforce. From Cambodia to the Philippines to Indonesia, common complaints are raised concerning a supposed influx of Chinese migrants, with resources being strained, cities being gentrified, jobs being taken, and local businesses being squeezed out by Chinese-owned ones.

Nor have Chinese investments always been entirely welcomed. Warnings have been raised about China engaging in ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ through the BRI; which involves issuing risky loans to poorer countries in order to create dependency and thus geopolitical influence. Sri Lanka’s granting of a 99-year concession on the Hambantota Port to China raised worldwide alarms about the possibly less benign aspects of Chinese financing.

Regional fears of China overriding the sovereignty of its smaller Southeast Asian neighbours have grown notwithstanding the real need for infrastructure. In an ASEAN-wide policy survey released in January 2019 by the Singapore-based ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 45.4% of those polled believed that China would become a ‘revisionist power’ intent on turning Southeast Asia ‘into its sphere of influence’. Another 47% saw the BRI as an attempt to bring Southeast Asian countries ‘closer into China’s orbit’, while an overwhelming 70% stated that their governments should heed ‘caution’ when negotiating BRI projects to avoid unsustainable debt.

One should not overstate the dangers however. A recent analysis by the Rhodium Group of 40 debt renegotiations made by China across 24 countries found only two examples involving outright asset seizures (in Sri Lanka and Tajikistan respectively). The vast majority of debt renegotiations often concluded with more equitable outcomes; often in the form of debt forgiveness, deferment of repayment, refinancing, and the renegotiation of terms. Beijing’s future outward lending is nevertheless expected to slow due to the large volume of debt renegotiations.

Over the past two decades, the development of extensive regional production networks centering in China has seen China and Southeast Asia become more integrated. In one sense this has made Southeast Asia’s economies vulnerable to spillover effects, as has been the case with the ongoing US-China trade tensions and China’s slowing domestic economy. On the other hand, external uncertainties may spur further integration as production relocates from China to ASEAN to avoid US tariffs. One 2018 study projected that trade with China will account for 20% of ASEAN’s total trade in 2035, up from 16.7% in 2017. China’s efforts in promoting greater connectivity within Southeast Asia through the BRI will also no doubt play its part in strengthening the historic linkages that have bounded China and its southern neighbors so closely together.