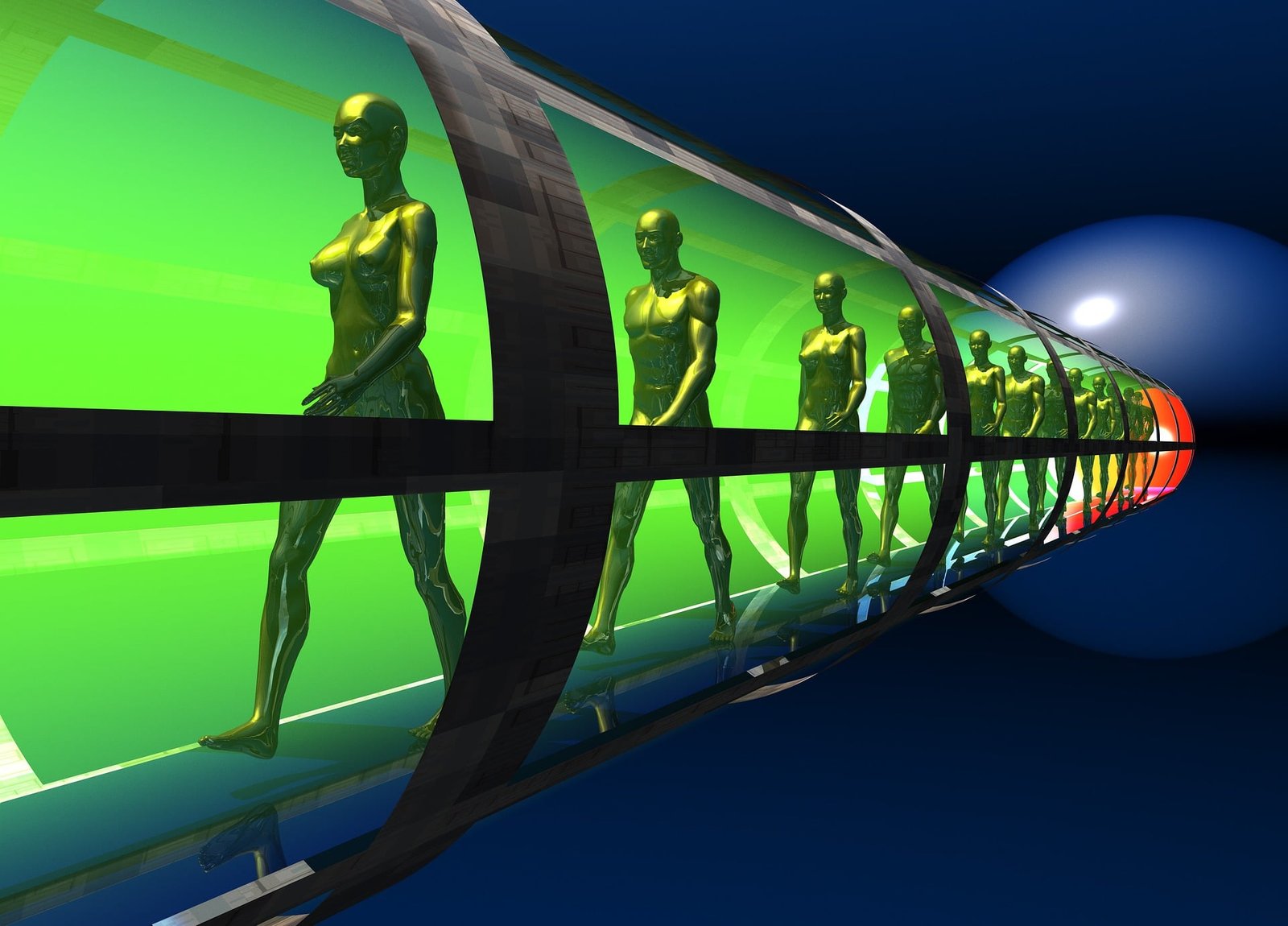

Conformism should be understood to be a dedication to achieving normalcy in the face of our own inherent deviancy from the norm.

The most widely accepted definition of a “conformist” is the following: “Someone who behaves or thinks like all other people do, rather than being diverse.”

Personally, I only agree with the first part of this definition: a true conformist behaves, but does not think, as all others do.

Indeed, if we look at the etymology of the verb “to conform”, we realize that its original meaning is merely related to what can be seen of things, to their shape, to their image. It is derived from the Old French “form”, which means “physical form, pleasing looks” or “manner”, indicating a feature of the body, or its behaviour, and the Latin “com”, which means “together”. Thus, etymologically, “to conform” means “to be similar”, “to make of the same form or character”. In other words, to appear and behave like the other.

Given that there is no way to directly access a person’s thoughts, the conformist is – intrinsically – always defined from the outside, phenomenologically. This sociological description, however, does not really help to understand them.

If I were Sigmund Freud, I would say that the conformist behaviour is just a symptom, and the analyst’s work is to search for what is hidden behind.

Now, what is the conformist masking? And from whom, exactly?

In 1951, the Italian journalist and writer Alberto Moravia published a novel entitled The conformist. The protagonist Marcello Clerici is an official of the Fascist government who desperately seeks, for his entire life, to achieve what he calls a condition of “normalcy”. In Moravia’s view, normalcy is the comforting sensation that follows unquestioned acceptance. In other words, a person feels “normal” when none of the aspects that characterize their life – which the person considers as natural traits of their personality and appearance – are called into question. Let us now imagine that you, as Marcello Clerici, are homosexual. You are a delicate, sensitive and effeminate child who is raised in Pre-Fascist times. By historical definition, everything you might feel as “normal” will never adhere to the institutionalized normalcy. In such a totalitarian context, two options are offered to you. Either you reach out, likely facing a miserable death, or you socially hide.

Here we are interested in the second option.

In practical terms, the simplest way of hiding is, for Marcello, to totally conform with the institutionalized normalcy. If you are an exuberant, creative homosexual boy, be a quiet, drab, heterosexual man. If you have a subversive mind, be complaint with the status quo instead.

As we will see, given that this psychological process is at least partially unconscious, it causes a psychic splitting. On the one hand, the conformist does not rationalize their condition; but on the other hand, what is unconsciously hidden, re-emerges in the form of emotional and existential symptoms.

Emblematic is the following passage from the novel: “[…] he thought, it couldn’t be said that he was convinced of the justice of Franco’s cause for reasons of politics and propaganda. This conviction had come to him out of nowhere, as it seems to come to ordinary, uneducated people: from the air, that is, as someone says that an idea is in the air. […] This simpatia, then, arose from deeper regions and demonstrated once more that his normality was neither superficial nor pieced together rationally and voluntarily with debatable motives and reasons, but linked to an instinctive and almost physiological condition, to a faith, that is, shared with millions of other people.” And also: “He felt […] a little sad. It was a mysterious sorrow, which by this time he considered inseparable from his character. He had always been sad like this, or better, lacking in gaiety, like certain lakes whose waters mirror a very high mountain that blocks the light of the sun, making them black and melancholy. One knows that if the mountain were removed, the sun would make the waters sparkle; but the mountain is always there and the lake is sad. He was sad like those waters, but what the mountain was, he couldn’t have said.”

But can a person avoid their tendency to adopt a conformist approach?

Fourteen years after Moravia’s effort, the Italian intellectual Pier Paolo Pasolini released his documentary Love meetings (Original version entitled Comizi d’amore, 1965).

The documentary is a collection of opinions that Italians shared, at the time, on the themes of sexuality and love, and how they related to them in everyday life. Among others, homosexuality still transpired as an unspeakable taboo, something that shocked the average Italian, and used to be rejected, leaving little room for discussion.

In light of the interviews he collected, Pasolini concluded that this behaviour of repulsion occurs because “the shocked person is uncertain, hence conformist.”*

Thus, conformism seems to take place as an instinctive defence mechanism from a feeling of uncertainty.

Anytime an individual faces a trait that is universally accepted and intrinsically embedded in the socio-cultural fabric but they do not feel “natural”, as the young Marcello Clerici did, they experience uncertainty.

Uncertainty is the emotive crossroad. Either the individual accepts the challenge, or they don’t.

Here is our clinical profile. The institutionalized normalcy dictates how the subject has to be educated. The subject feels a lack of adherence to the institutionalized normalcy, becoming uncertain. This first, philosophical uncertainty gives them the chance to reject the status quo, establishing a critical dialogue within the socio-cultural milieu. If uncertainty is embraced, the subject becomes an anti-conformist in a literal sense. If uncertainty is refused, the subject becomes a conformist. Seeking continuous consolidation and satisfaction of their desire for acceptance, the conformist conforms to the institutionalized normalcy. They are now the most convinced individuals on Earth: they are certain that they know what is good and what is bad, what is true and what is false. However, despite this certitude, their knowledge is indeed superficial, because it is not achieved through critical analysis. Given that they base their life on undetailed, superficial knowledge, they are in fact on the same intellectual level as ignorant people are.

Once more, in Alberto Moravia’s words: “A belief that has been achieved through reason and an exact study of reality is elastic enough never to be shocked. But a belief received without analysis of the reasons why it was received, accepted through tradition, laziness, passive education, is a conformism.”*

Coming back to the opening definition of a “conformist”: a conformist does not think, because they unconsciously internalize the socio-cultural apparatus as a whole, without questioning it.

In Nietzschean terms, the conformist does not proceed beyond the stage of the camel, thus unconsciously picturing their life as a never-ending sacrifice.

In Freudian terms, they are constantly overwhelmed by an excessive power of the Superego, which represents their ideal of certainty. In this sense, from the behavioural point of view, the conformist is a “shell” dogmatist: the institutionalized normalcy functions as a “God”, and they unconsciously behave as if they trust in it.

In the end, Pasolini offers us an excellent concluding remark: “Conformism [as] the stubborn certitude of the uncertain”*, where stubborn stands for unconscious, and certitude for dogma.

*Taken from a conversation between Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alberto Moravia and Cesare Musatti, recorded for and appeared in Love meetings.

Simone Redaelli is a molecular biologist on the verge of obtaining a doctoral title at the University of Ulm, Germany. He is Vice-Director at Culturico, where his writings span from Literature to Sociology, from Philosophy to Science.

Simone can be reached on Twitter: @simredaelli

Article Discussion