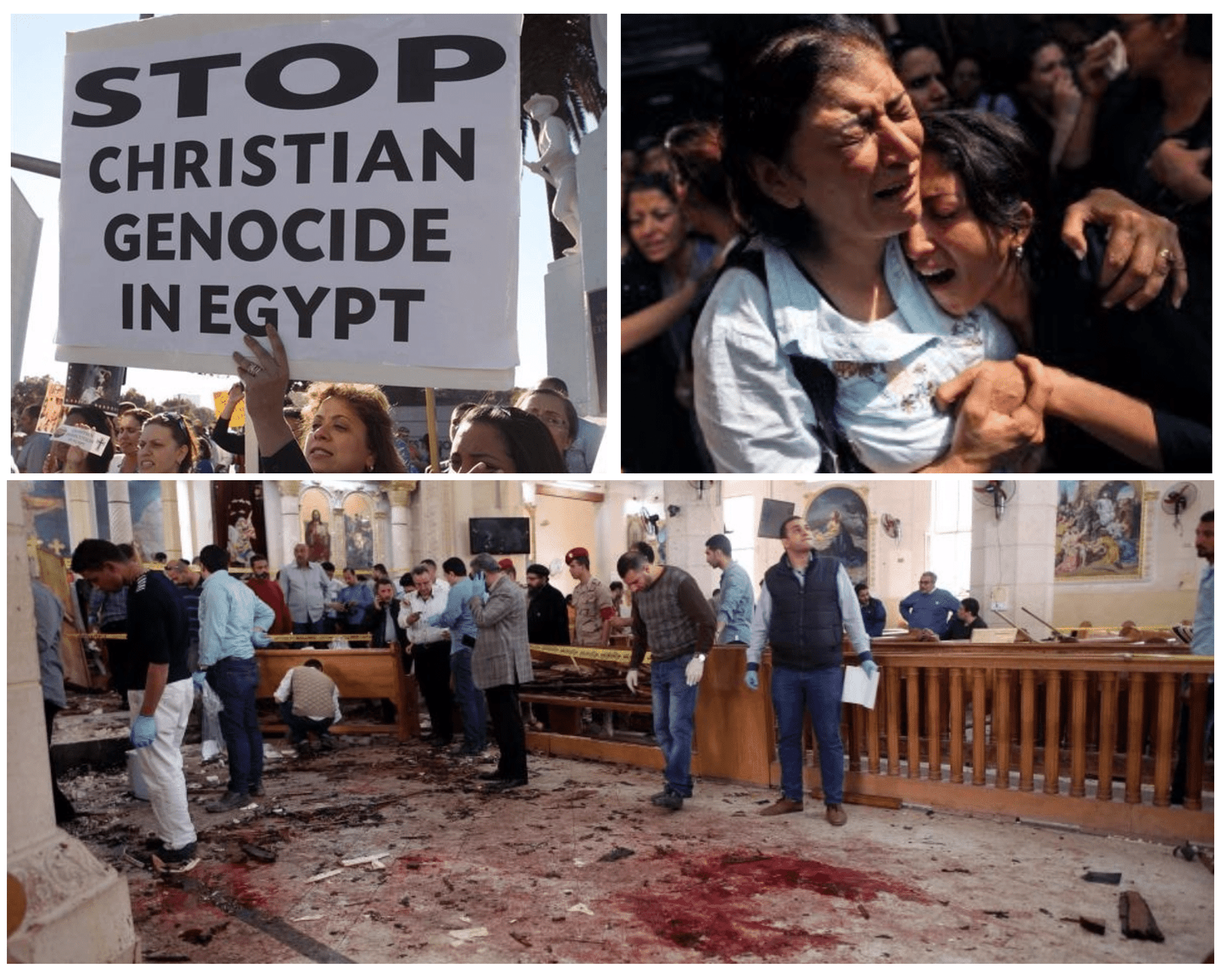

The Palm Sunday massacres in Egypt, which killed at least 44 people and left over 100 wounded, is only one in a series of attacks on the country’s Christian communities. The tragedy attracted media attention to the plight of the religious minority, object of escalating Islamist violence. Human rights groups warn that the threat of persecution is only worsening in the unstable region and that Christians are finding themselves in an increasingly precarious situation. Coptic Christians make up 10 per cent of the country’s population. The volatile political climate has exposed their troubling vulnerability. Since the 2011 ousting of President Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian Christians have consistently been the victims of attacks, whether as part of an effort to intimidate them from participating in the political scene or as part of a wider, regional persecution in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Estimates place the number of Christians who have fled their homeland since the 2011 revolution at 100,000. Fear of reprisals after the resignation of Mubarak, whose dictatorship had previously kept extremism in check, resulted in a veritable exodus from the beleaguered country. The threat of fanaticism loomed large in a post-Mubarak era that saw hitherto excluded groups avail of greater freedoms. When the Muslim Brotherhood succeeded in taking over Parliament, it lent further credence to the suspicion that the revolution acted as a catalyst for increased sectarian strife.

On March 4, 2011, a mob, enraged by a rumoured affair between a Muslim woman and a Christian man, set fire to a church in Atfih. The ensuing protests against the act resulted in the destruction of Christian homes and businesses.

Summer of 2011 saw several incidents of anti-Coptic violence. In May, a mob humiliated a 70-year-old woman, stripping her naked in public because of her son’s alleged affair with a Muslim woman. On July 17, a Christian man was killed after an argument escalated between Muslim and Coptic children. Between June and July, mobs destroyed Coptic homes in response to a rumour that they were being used as churches. In Alexandria and al-Fashn, the same: churches and places purported to offer Christian religious services were attacked.

On October 9 of the same year, the military employed deadly force in response to demonstrations against official inaction in the face of violence and discrimination motivated by anti-Christian sentiment. What resulted is known as the Maspero Massacre in which 28 persons were killed, most of them Coptic protesters.

Sinai has seen repeated attacks, becoming a front-line in the fight between the army and Islamic militants. Since 2013, when President Morsi, who hailed from the Muslim Brotherhood and emboldened its members, was overthrown in a military coup, Islamists have escalated their attacks against both the military and Christians, whose support of President el-Sissi, former army chief, has made them prime targets. In December 2016, twenty-nine Christians were killed and several dozens injured when a suicide bomber blew himself up in a Cairo church.

More recently in February of 2017, a Coptic Christian was shot inside his home, in front of his wife and daughter, prompting another wave of panic that resulted in numerous families fleeing the area. Just a day before, militants killed a Coptic man and burned his son alive. What is more, there have been drive-by shootings and home raids of Christian families in el-Arish.

More recently in February of 2017, a Coptic Christian was shot inside his home, in front of his wife and daughter, prompting another wave of panic that resulted in numerous families fleeing the area. Just a day before, militants killed a Coptic man and burned his son alive. What is more, there have been drive-by shootings and home raids of Christian families in el-Arish.

ISIS released a video vowing to kill more ‘infidels,’ whom they accuse of siding with the West against Muslims.

The Christians of Egypt are a minority in their native country, but they make up 90 per cent of Christians in the Middle East. Drawing attention to their plight means drawing attention to religious minorities in a combustible region of the world in which they are quickly becoming akin to endangered species. It is in the interest of humanity as a whole to protect minorities; the extinction of one means the imperilment of all. The presence of minorities in any society leads to greater open-mindedness and acts as a mitigating force to counter policies that may be exclusionary. The first sign of totalitarianism is the stripping away of minority rights. In August 2016, a law was passed in Egypt restricting the construction and renovation of churches, allowing for governors to deny building permits without recourse and including provisions that would subject the matter to mob-rule under a pretence of ‘safety’ concerns. What sort of message does this send if not that discrimination against Christians is lawful and justified?

The international community must do more to stop terrorists – and the states that sponsor them – from stamping out religious diversity in the Middle East. This starts with being unapologetically vocal regarding violations on the part of governments that, directly or indirectly, legitimise violence against minorities.

[…] other religious minorities are persecuted (including Bahá’ís, Ahmadis, Yazidis, Kurds, Coptic Christians, Sufis, and Hindus). Given that secularism protects religious freedom for practitioners of all […]