(This is an expanded version of an opening statement given by Helen Pluckrose on the 28th October 2017 at the Battle of Ideas festival hosted by The Institute of Ideas and supported by Conatus News).

Postmodernism bears significant responsibility for the post-truth society, perhaps even more than we realise.

Post-truth is not simply lying. It’s a very specific phenomenon in which facts just aren’t considered important and truth is based on appeals to emotion. We saw this when the Russian political scientist, Alexander Dugin said, ‘Truth is a matter of belief … there is no such thing as facts’. Similarly, a Bush adviser said, in response to the assertion that solutions should be based on discernible reality, ‘That’s not the way the world really works anymore…We create our own reality.’ In a post-truth world, reality is constructed, knowledge is subjective, and truth is whatever our intuitions say it is. This is also the hallmark of postmodernism. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

The postmodern view of knowledge stands in direct opposition to that which defines Enlightenment liberalism, which enabled our ascent out of medieval society into the advanced technological world we enjoy today. Jonathan Rauch summarised the relevant features of Enlightenment liberalism 25 years ago, arguing in favour of ‘liberal science,’ by which he meant a system in which anyone can evaluate truth claims on their evidence and reasoning, leading to the sound ideas winning out and the bad being marginalised. This principle is now under threat. Under the post-truth playbook of postmodern social theory, if one can replace evidence and argument with ‘As a member of identity group X, I feel that the truth is…’ or if one can disparage evidence and reason or simply ignore the need for it, the whole basis of truth is reset. Postmodernism, thus has been deeply influential in contributing to a cultural norm where this is acceptable. It has gone a long way towards creating a culture in which facts can be relative, expertise is suspicious and where personal truths and narratives satisfying and validating to a cultural group can simply be claimed to be true.

“The postmodern view of knowledge stands in direct opposition to that which defines Enlightenment liberalism, which enabled our ascent out of Medieval society into the advanced technological world we enjoy today”

Most left-wing academics will argue that postmodernism is over. It is not. Rather, it has evolved. Academics who make this claim are usually referring to the first high deconstructive phase which burnt itself out fairly quickly because it was neither comprehensible nor user friendly. It broke everything down and rendered it ultimately meaningless. However, postmodernism acted like a virus – the first attack of it was most extreme and infected very few people. It then came back in the more explicitly politicised forms of intersectional feminism, queer theory, postcolonial theory and critical race theory. These had popular appeal because they could be distilled into ideologies that were user-friendly and could be acted upon.

The new wave of critical theorists took postmodern ideas of gender, race and knowledge as culturally constructed by discourse. However, they argued that social realities did exist, and that society has been built in hierarchical systems which privileged some groups and their systems of knowledge above others and that this must now be remedied. Consequently, science, reason, evidence & expertise have been designated the property of white, western, heterosexual, wealthy men, thereby diminishing the achievements of all the scientists, thinkers and experts who do not fit the description. To continue to support the fruits of the Enlightenment is therefore understood to perpetuate sexism, racism, homophobia and colonialism.

There was a lot more to postmodernism than this, of course. Postmodernism was a massive, multidisciplinary phenomenon which covered great intellectual terrain. However, when considering its impact on a post-truth society, we need to focus on its general relationship with the truth. This is founded in such ideas as Foucault’s that knowledge is a construct of power. Or Lyotard’s that science is just one language game that cannot legitimate itself. Or Derrida’s that there is no objective reality corresponding to language, “There are only contexts without any center of absolute anchoring”

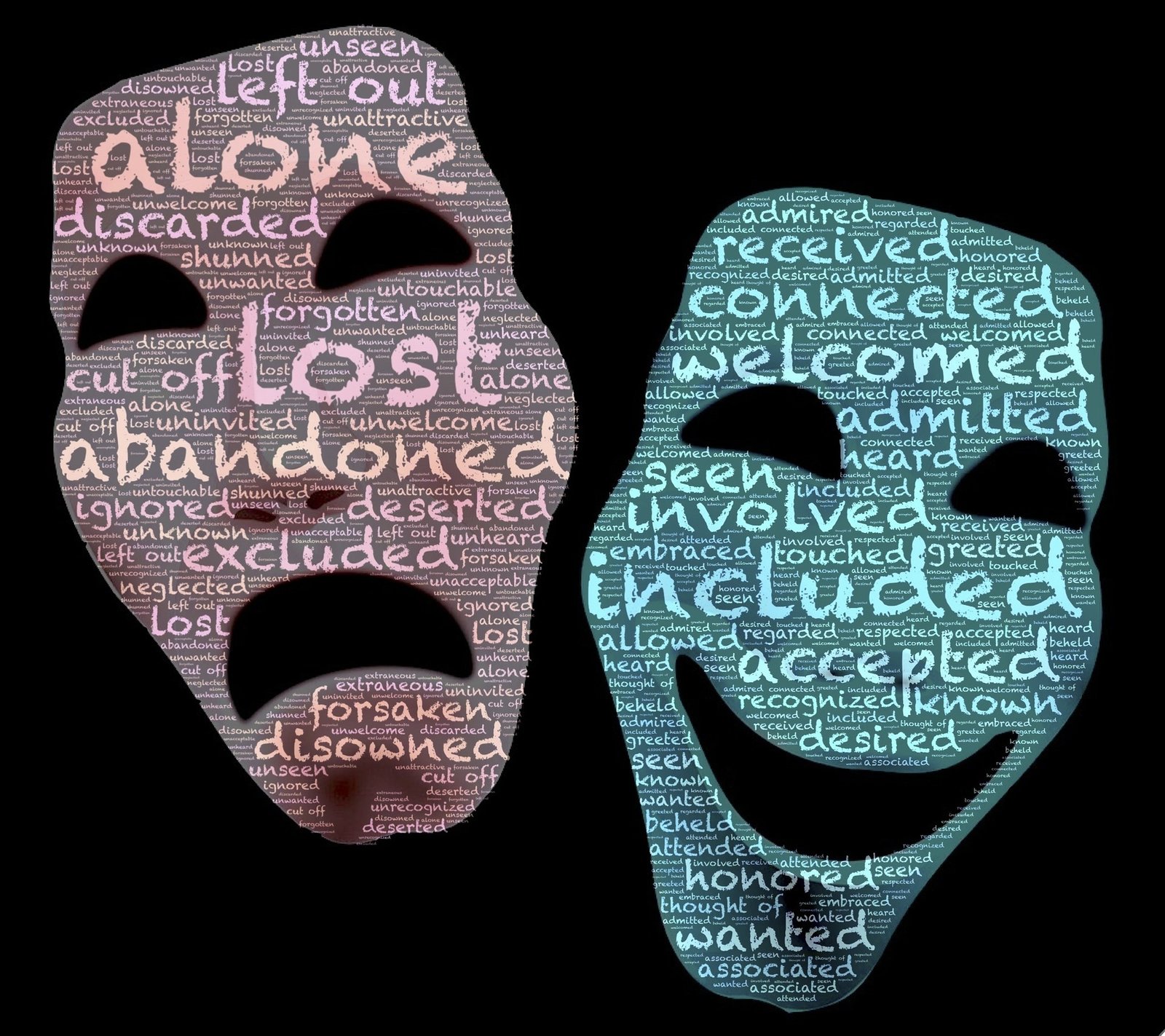

The defining quality of postmodernism is a move away from the aim for objective truth both morally and factually. It’s a turn from a shared objectively knowable world to a world in which we’re all situated by our identities and this determines what we can know. Of course, this results in identity politics. It is difficult to overestimate how profound an effect postmodernism has had on the political left or the extent to which leftist identity politics have both motivated and legitimised rightist identity politics. Even so, it would clearly be a mistake to claim that rejection of objective truth and embrace of identity politics originated with postmodernism. These are consistent human failings. History provides ample evidence of humans being tribal and preferring satisfying stories over reality. Religion is a prime example of this. It would also be an error to claim that postmodernism is the sole cause of our post-truth phenomenon.

“The defining quality of postmodernism is a move away from the aim for objective truth both morally and factually”

There are other highly significant factors. Our loss of confidence in institutions and in expert knowledge following scandals and catastrophe has been a profound motivation for eschewing evidence-based epistemologies. Social media has been a mighty tool enabling the spread of fake news and ideologically-motivated narratives. The internet doesn’t discern between facts and falsities. We have to do that. But our ability to do that is precisely what has been compromised intellectually. The universities are complicit here.

Even if we concede that there are significant motivations to reject objective notions of truth and new technological tools enabling us to do so much more easily which have nothing to do with postmodernism, we cannot afford to overlook what is at the root of the problem – the shift in the way we think. We have gone from expecting a truth claim to have evidence and a reasoned argument to expecting it to confirm our bias. It should be clear that postmodernism’s identity politics and denial of objective truth have played a role in creating our current problem with identity politics and denial of objective truth.

This is not a problem confined to esoteric arguments between intellectuals. Liberal academia has great cultural power and historically been largely responsible for maintaining the expectation that truth claims will be reasonable and evidenced. Infected by postmodernism, this epistemic relativity has seeped into mainstream liberal culture through politics, philosophy, media, art and social justice movements. A whole generation of students were exposed to these ideas and went on to become leaders of various industries. These key ideas were distilled into bite-sized, user-friendly chunks for activists and passed into the social conscience of mainstream society. They traded on the good name of the civil rights movement, second wave liberal feminism, and the Gay Pride movement.

Thus, these developments, for all their potency and widespread acceptance and normalisation, are, in fact, relatively recent. I was there when feminism abandoned universal liberalism and turned towards identity politics. I regularly have young people tell me that everyone has their own truth and that there are things I mustn’t talk about because I am the wrong demographic. This is the progressive zeitgeist now but what it threatens is regression.

With the universities having seemingly abdicated their role as rigorous, evidence-based producers of knowledge accepted provisionally and ever open to revision, the door has been opened wider to myriad other forms of personal and cultural narrative, motivated reasoning, confirmation bias and flat-out lies and fabrications. Narratives are back. Group perceptions have validity again.

This can be seen in left-wing intellectuals who argue against science and expertise as just a white, western, masculine way of knowing but we also see it elsewhere. We see it in those who would foreground religious narratives and faith-based thinking above objective knowledge. We see these narratives in the most extreme interpretations of Friedrich Hayek who was sceptical of rationalism and knowledge-as-propaganda and in certain admirers of Jordan Peterson who in Maps of Meaning sees objective truth as constructed in narratives and foregrounds an effective and pragmatic ‘truth’ found in the mythic world.

These narratives can be read in a very moderate way as a warning against bias and naive trust in expertise and a recognition that group knowledge can sometimes be fuller or more meaningful on a moral or emotional level. They can also be read in support of radical scepticism of objective knowledge and populist rejection of expertise. That is increasingly how they are presented to me.

With postmodern ideas acting as an accelerant, we are creating an era in which truth is understood to be anything we can claim and rationalise pragmatically according to political, ideological or personal aims. The danger here, apart from the generally catastrophic effect on society’s perception of truth and knowledge, is that confidence in the universities is being undermined. This is making them vulnerable to attacks on scholarship generally from the far-right and difficult to defend by reasonable, liberal centrists and lefties. We need to counter this by reinstalling an expectation that truth claims will make sense, be presented in the form of a reasoned argument and accompanied by evidence. Universities need to prioritise this again because without it, we risk returning to a thoroughly pre-modern world or a totalitarian one. We need them to do this now.

Posted by Nikkita Adler

14 January, 2018 at 7:48 pm

Great article

Posted by elee

5 January, 2018 at 2:19 am

Hey I think I get this stuff......UNESCO's declaration that Jerusalem never ever had anything to do with any Jews is a postmodern assertion that is corroborated by Its sheer intuitivity to a billion plus Muslims. And since Herbert Marcuse is of the generation's preferred ethnicity and I'm not, I should accept at best dhimmitiude and not raise my voice or ring a bell for my services. Right? Yes I'm catching on. What a self-evident idempotent truth it all would be, if there were truth or falsity to anything.

Posted by Alex S.

5 January, 2018 at 1:43 am

As a big fan of Peterson generally, and someone who has probably listened to nearly all his publicly available speaking in the last couple years, I thought the point about objective truth landing subsidiary to pragmatic truth was actually well-made near the end of your piece. It's an interesting note to make, since he himself loathes post-modernism but holds a view which might coincide with it on some depending on your interpretation. Good article! Hopefully more people on the left realize they're tearing down the foundations in the next few years and we can right this ship a bit, pun possibly intended. :)