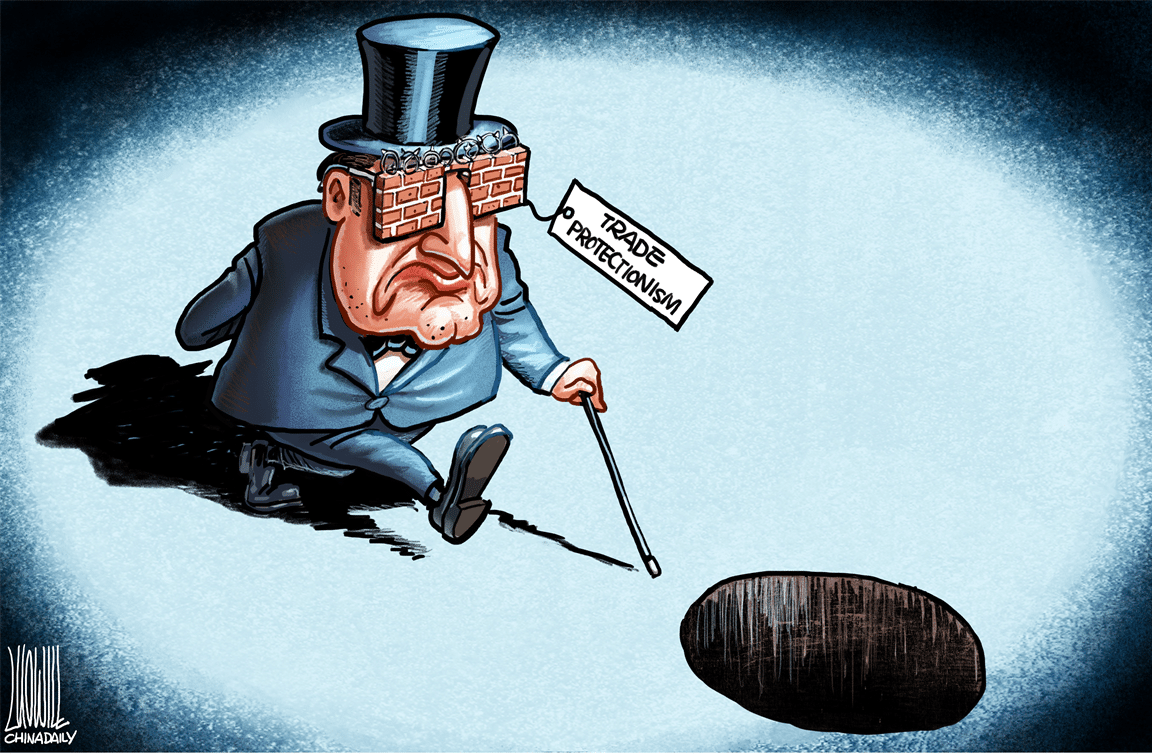

If we want economic growth in an era of globalisation, then we must focus on free trade and decentralisation of the economy, not protectionism.

It is a truth universally unacknowledged that free market enterprise was a major factor in drastically reducing poverty worldwide in the twentieth century. The natural extension of this concept is globalisation, “the state of being globalised; especially: the development of an increasingly integrated global economy marked especially by free trade, free flow of capital, and the tapping of cheaper foreign labour markets”, as defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary. A lofty goal which attracted an almost unanimous consensus among economists.

Most political figures and economics buffs still agree on principle, but in various countries across Europe and North America the general public seems to be growing ever more divided on the issue. A prime example is the delay of CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement), a Canada-EU trade deal, by the regional government of Wallonia, a small region in Belgium, amidst fears of environmental repercussions and potential losses of jobs due to outsourcing.

However, the most striking example would be President Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership), a trade agreement signed by 12 countries (now 11), and endangering the adoption of TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership), a EU-US potential trade deal.

All of this, and more, is happening amidst a public backlash against globalisation, which fuelled major political events and political upsets, such as Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. During the 2016 US presidential election, Bernie Sanders repeatedly criticised his opponent on her support of free trade, to the public’s delight.

The case for protectionism is the easiest to make when one is angry. The word has a certain flavour that makes us believe that nothing bad could possibly come out of it. The most famous measure to this end is imposing tariffs, taxes that make foreign goods more expensive and thus less competitive, giving a boost to domestically produced goods and services. Tariffs are a pat on the back for local producers and businessmen. But the measure itself is almost never productive. Take the case of Japan, for example. Because of the protectionist policies imposed on rice, the Japanese people paid exorbitant prices for the commodity, much more than anyone else in the world. It was all due to the short supply of locally grown produce. Protectionism made the farmers satisfied. But their satisfaction was heavily subsidised at the expense of the Japanese consumer.

Such measures are usually implemented in times of crisis. If we are at war with a country, or really upset with them, we establish economic embargoes. We stop selling goods and services to them, as punishment. Conversely, tariffs prevent others from selling products to us. In every meaningful way, tariffs do to us in times of peace what we do to others in times of war.

“In every meaningful way, tariffs do to us in times of peace what we do to others in times of war”

On the other hand, anecdotal evidence for the efficiency of the free market is easy to find. Whether we look at West Germany back in the day, Japan before its economic surge, Colombia in recent years or Israel, we observe that they developed and thrived when their markets encouraged competition and economic freedom and stopped thriving when the opposite was true. The evidence is in, but then why have some people grown off free trade?

Most opponents claim to be getting more and more upset about the perceived disadvantages of globalisation: outsourcing, the lowering of wages, deregulation. Perhaps ethics should be more often taken into account when signing a trade deal. Mutually benefiting deals driven by self-interest just won’t do, they say.

The most ardent criticism of free trade comes from the Left, in a stunt that drags the Left back to its original twentieth century roots, when socialists and democratic socialists had no particular inclination to be excited about multiculturalism or unencumbered movement of capital and people. On the contrary, the traditional socialists were protectionists par excellence.

The arguments against free trade are bizarre reiterations of the age-old arguments against capitalism. It all seems like a resurgence and a rebranding of the anti-capitalist sentiment, a process fuelled by the bitter realisation of more and more people that they won’t have the same opportunities and economic mobility as their parents and grandparents.

The call-out culture on the Left is another contributing factor. Many people’s feelings are intensified by a mystical need to preserve their own or their nation’s moral purity. Friedman ironically observed in his book, The World Is Flat, that “pampered American college kids” who, “wearing their branded clothing, began to get interested in sweatshops as a way of expiating their guilt.” In the same book, Friedman affirmed his capitalist peace theory. He famously stated that if two countries have the McDonald’s franchise, then they would never go to war with each other. In essence, what that is saying is that attracting foreign investments and job creators while affirming their position in the global market is something that no country would desire to jeopardise unless it had shady agendas.

Whatever the direction of this debate, one thing is clear: free trade and decentralisation are here to stay. One need not look too far to notice the benefits of voluntary human cooperation which exists outside of official or governmental bodies, from Uber, the largest cab company that owns no cars, to Bitcoin, the marvel of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology.

The world is ready to change. And at the heart of this change will be change itself. Money went from shells to metal and then to paper, and now it’s transitioning towards dynamic coding. Just a month ago, Singapore started trading its national currency using a blockchain technology called smart contracts.

The good thing about this debate is that history offers large reserves of wisdom on the topic. Here are some simple observations. Protectionism always ends up harming the people it claims to protect. The free market is a powerful engine of economic growth. Technology will keep on building and rebuilding the world.

“Protectionism always ends up harming the people it claims to protect”

The fact that change is coming should make us ask serious questions. After all, the last thing we want is a poorly managed transition. Perhaps the wisest thing to remember is that economic freedom will always be necessary if we want our society to thrive, but we should always bear in mind that with freedom comes responsibility.

Article Discussion