What can the history of Arab Socialism – Ba’athism – tell us about the circumstances in which nationalism and socialism are united in one ideology?

Previously, we have examined the question of how closely various left-wing nationalist movements have echoed or deliberately drawn from fascist influences. Today, we explore one of the most famous and controversial ideologies of the 20th century, which paved the way for both Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Saddam Hussein in Iraq: Ba’athism.

Arab Socialism

Arab Socialism was a term first used by Michel Aflaq, the founder of Ba’athism and the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. He used it to distinguish the amalgamation of socialism and Pan-Arabism, which was the political ideology of the Ba’athists, from the international socialist movement. Aflaq claimed that whilst “there is neither incompatibility nor contradiction nor war between nationalists and socialists”, socialism would only come when Arab unity and liberty was properly achieved. After all, fighting against imperialism, entrenched class structures and for social justice was socialism, as he saw it. Aflaq was clear that “we want socialism to serve our nationalism”.

Arab Socialism owed little to Marxism and was, according to a Soviet critic, “just a hazy outline on a barely developed ideological negative.”1 The party constitution called for state ownership of large industry and transport, as well as public utilities and natural resources. Prominent features of early Ba’athist thought included restrictions on land ownership and state supervision of the economy to prevent the exploitation of one class by another, before the eventual abolition of class differences. However, the Ba’athists were clear that Arab Socialism was not communist, the Ba’athists did not look to Marx or Lenin and the internationalism of communism was clearly at odds with the primary focus of Ba’athism which was, of course, Arab nationalism. They believed that nationalism, not class struggle, was the central tenet of human history.

By the mid-1950s it was possible to see some thawing of relations between Arab Socialism and communism, with leading Ba’athists such as Jamal al-Atassi urging the party to learn from the experience of socialist countries in constructing their societies. Ba’athist literature also began to use more socialist terms, such as ‘masses of the people’ and the emphasis on class conflict increased. However, all of this was used to promote the idea not of a socialist revolution, but instead of a revolution that threw off oppressors to establish a united Arab society.

Jordanian Ba’athist Munif al-Razzaz wrote ‘Why Socialism Now’ in 1957 and elevated the importance of socialism in the Ba’athist movement, stressing the interdependence of the Ba’athist slogan of ‘Unity, Liberty, Socialism’. For al-Razzaz, socialism and nationalism were both necessary to secure freedom, and nationalism did not necessarily have to come first.

Ba’athism advocates a one-party government for an unspecified period of time, during which an enlightened Arabic society will supposedly develop. However, the two Ba’athist states which have existed, in Iraq and Syria, both proved to be authoritarian in nature and committed atrocities against their own peoples. Criticism of their ideologies was not permitted. Whilst there is some argument that these governments should be described as ‘Neo-Ba’athists’, because they strayed from the early Ba’athist principles of Aflaq, this can be seen as the usual deflection from proponents of a failed movement. Ba’athism as a political ideology was largely used as a justification by those intent on power at all costs.

Syrian Ba’athism

The Ba’ath Party which took power in 8th of March Revolution in Syria had already discarded their pan-Arab beliefs, instead elevating socialism and claiming that pan-Arabism was the means to the socialist ends, rather than the main goal in itself. Al-Razzaz argued that the form of Ba’athism which now dominant involved an authoritarian centralised government which rested on military power, and was therefore a ‘military Ba’ath Party’ as opposed to the real Ba’ath Party. The 1966 Syrian coup saw the ruling National Command of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party removed from power by a union of the party’s Military Committee and the Regional Command. Subsequently, the founders of Ba’athism themselves declared that Ba’athist politics in Syria were truly at an end.

Syrian Ba’athism now embraced more western ideas of socialism, elevating class struggle and inviting the Syrian Communist Party into government. Close relations with the USSR followed and attempts were made to restructure the economy with state ownership of industry and government restructuring of agriculture.

However, since the ascendancy of Hafez al-Assad in 1970, Ba’athism in any form has been superseded by ‘Assadism’. Syria has been under the control of the al-Assad family and is a personal government which relies on the guidance of the Assads. Syria is now thoroughly nepotistic, and the party along with the military, has undergone a process of Alawitisation. This has seen elevation of a religious minority, the Alawites, far beyond their proportion of the population, which as a sect of Shia Islam, has fed Iranian support for the regime.

Ba’athist ideas of pan-Arabism and socialism have been replaced by the domination of a minority, bolstered by false socialist slogans, whilst the ruling family and those loyal to them have amassed a fortune at the expense of the Syrian people.

Iraqi Ba’athism

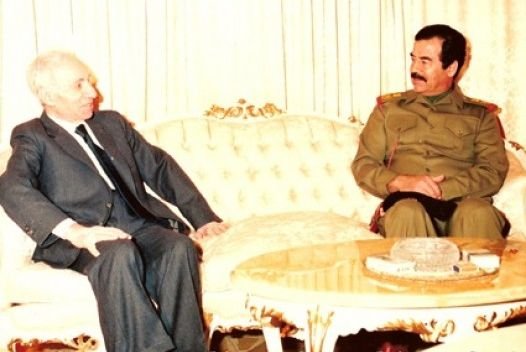

The Iraqi Regional Branch of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party gained power in the bloodless 17 July 1968 Revolution. Although the coup was instigated by non-Ba’athist military figures, the party was invited in to give a veneer of legitimacy to the revolution and quickly took power for themselves. Originally Ba’athist Iraq was led by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr with Saddam Hussein as one of his deputies. By the mid-1970s Saddam was the de-facto leader of Iraq, and in 1979 his position was made official.

Saddamism or Saddamist Ba’athism was officially described as a distinct variation of Ba’athism which embraced Iraqi nationalism and placed Iraq at the centre of the Arab world. A militarist regime, all political discourse was couched in military terms. Saddam was, like the early Ba’athists, critical of Marxist-Leninism, describing the Iraqi Ba’ath Party as a popular revolutionary movement that did not need such an ideology. He was, however, an admirer of Lenin himself, and the way that he was able to adapt Marxism to the Russian context. This was a theme with Saddam – praise for communist leaders such as Castro and Tito who focused on Nationalism as well as Communism.

Whilst accusation of fascism or being ‘fascist-adjacent’ have long dogged Ba’athism, it seems more likely that the original party mined both fascist and socialist movements for useful ideas on how to organise and attract support. Saddam Hussein was alleged to have admired both Hitler and Stalin, not necessarily for their policies but more for their abilities to organise and control their respective countries.

Although Ba’athism has had many adherents, its political history is dominated by ruthless, power-hungry pragmatists who used nationalist and socialist sentiments to solidify totalitarian rule over their countries. Any genuine Ba’athist philosophy has been eclipsed by the simple desire to use populist messaging for propaganda purposes.

Article Discussion